Poetry Reviews by Gregory Woods: Mute and Handmade Love

Mute

MuteBy Raymond Luczak

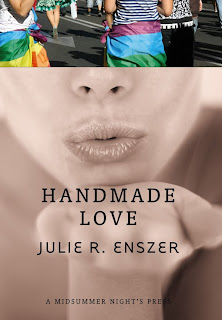

Handmade Love

By Julie R. Enszer

Published by A Midsummer Night’s Press

A Midsummer Night’s Press has published several poetry collections in this diminutive but handsome format (roughly six inches by four, in old money). You can fit each volume into a tiny pocket without disrupting the lines of your tailoring. But don't be deceived by this convenience into thinking that because the books are small they are insubstantial. They are full-length collections aiming to pack a punch. Prominent among them is Brane Mozetic’s remarkably vigorous and intelligent collection Banalities, which the press issued at the end of 2008.

Raymond Luczak has had a distinguished career in the USA as an advocate for deaf people’s rights, within both the lesbian and gay subculture and the broader range of communities. I foreground this theme, just as I do his gayness, because he does so himself, both in this book and elsewhere. He has written drama, fiction, poetry and non-fiction for many publications about sexuality, disability and—well—life itself. He is also a film-maker. Each section of this new book of poems has an epigraph about silence, but he does not go very far in exploring this. He keeps mentioning it, to be sure, but that is my point: that is not silence. His prolific verbalism is hardly ever modulated with moments of silence. Everything is about expression—not a bad theme for a poet, but one to be taken with a pinch of salt. Poets learn the limits of language.

His didactic opening poem, ‘How to Fall for a Deaf Man’, presents itself as a manual of courteous flirtation, full of practical advice (‘Do not ask him the sign for FUCK. / He is tired of showing how’), but, over six lively pages, proves more interesting as a cheerful record of the erotic life as lived by the deaf among the hearing. Intercourse (let’s call it) takes place amid a flurry of expressive gestures—as if the natural flexible-wristedness of gay men had been accorded an additional élan by the muffling of voices. Sad to say, I think Luczak spoils this poem with its bathetic closing couplet: ‘Discover how much water and sun love takes / to grow, and how much can sprout in your hands.’ The image is not particularly fresh and appears, here, as a distraction from the poem’s celebration of the social and erotic.

Desire is interlaced, in other poems, with loss and grief in a way that we have come to expect from the gay liberationist generations that survived the worst emergency of AIDS and the wave of homophobia that worsened it. Luczak’s elegies commemorate not only individuals but also the optimism of an era whose hopes were so violently dashed—if, perhaps, to be partially and belatedly fulfilled around the turn of the new century. These moods are part of a general subcultural record.

Restricted hearing and signing are Luczak’s constant themes, but I looked for something more distinctively ‘deaf’ in matters of form and technique. The deafness of a poet is intrinsically no more paradoxical than Beethoven’s or, more recently, the percussionist Evelyn Glennie’s. The paradox, if any, is more likely to be in my response, as a hearing reader of poetry (even when reading in silence). I find myself wanting there to be a qualitative difference—evidence, perhaps, of an increased sensitivity to the sound of words, or to their appearance on the page—in the way he uses language, or at least in the way he reflects on its use. This may be to place an unreasonable demand on him, but why should that stop me making it? I expect a great deal of the poets whose work I am going to learn to like, and what I expect of them may be contingent on all sorts of external factors. I am not an equal opportunities reader.

Speaking of which, I really cannot pretend to have liked Julie R. Enszer’s book. For a start, a passage from the poem ‘Constantin Brancusi’s The Kiss’ filled me with misgivings: ‘This is what I despise about poems— / the way they isolate / distill life to only the good parts / they never capture this— / harsh words in morning or constipation or warts’. This suggests that the speaker (for let us suppose it is not Enszer herself) has not read much poetry. It is certainly hard to believe that an American poet could say such a thing in earnest. Does she not remember the ‘venereal sores’ in the Preface to the 1855 first edition of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass? That said, I rather liked the poem ‘Further Evidence’, which is witty in both form and mood: a villanelle about a worrying vaginal discharge.

The collection’s title contains a decent Sapphic pun (handmade/handmaid) that promises a much lighter touch of sexually playful language than she delivers. ‘Morning Post’ is little more than the superfluous over-extension of an unoriginal erotic joke. ‘I know what women want to eat in the morning,’ it begins, elaborating on the fry-ups the speaker used to prepare on Sunday mornings for her straight girlfriends after their Saturday-night assignations with men. But she finally met a woman who had, like her, other oral pleasures in mind—to eat not bacon and eggs but pussy (her word). ‘I know what women want to eat in the morning,’ the poem ends, having taken seven quatrains to make a point that a haiku might have made with greater poise. Unless we are meant to read it as signalling that the poem itself is in dire need of a break from the mundane, a line like ‘Sauces can satisfy the need to break from the mundane’ really does not deserve to have survived the drafting process.

More often than not, her verse is prosy—but without the rigorous control of form and precision of lexis that makes its prosiness seem appropriate to anything but prose. Time after time, she drifts off into an essayistic mode that lays claim to an engagement of the emotions without showing any spark of passion in the language: ‘Now, I have more investment in sex as an older person, / becoming one myself, though, I hasten to add, not nearly / as old as you’; ‘Perhaps our innate / biological being compels us to couple, demands / that we find a spiritual, emotional, and sexual mate’; ‘I want to respect your gender identity and not reconsider / my own sexual orientation and erotic predilections’. I am not sure that such sentences are even elegant enough for a didactic essay, let alone a love poem. In ‘Dear Donald’, imagining herself in her sixties, having sex in the afternoon, she says ‘It is deeply pleasurable and erotic’. If a poet cannot convey this dull message by tone alone, let alone by sensuous imagery, she is in trouble. In a poem on the eponymous friends in the sitcom Will and Grace, she says she has ‘No words to describe the unlikely partnership, // but ample support, chaste affection, retained / sexuality’. (Retained?) In one love poem she refers to girly nicknames as ‘diminuitive feminizations’ [sic].

Perhaps her method works out at its best when she really, consciously and ostentatiously, strains the prosaic syntax, as in ‘Making Love After Many Years’, which, after a brief opening statement (‘It isn't easy’) otherwise consists of a single long sentence that sprawls out over two pages. This, at least, looks deliberate. Which is more than can be said for her collection’s shoddy proof-reading. One poem even has a phantom footnote number, but no footnote (presumably, to explain the word ‘hooning’, in case her use of it is too smudgy for the reader to follow). Feeling in need of a tonic—and yearning for radicalism of content strengthened, rather than held in check, by rigorously disciplined technique—I ran off to my bookshelves for a volume of Marilyn Hacker.

Gregory Woods is Professor of Gay and Lesbian Studies at Nottingham Trent University. His critical books include Articulate Flesh: Male Homo-eroticism and Modern Poetry (1987) and A History of Gay Literature: The Male Tradition (1998), both from Yale University Press. His poetry books are published by Carcanet Press. His website is http://www.gregorywoods.co.uk/

Labels: A Midsummer Night’s Press, Gregory Woods, Julie R. Enszer, Poetry Review, Raymond Luczak

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home